Key Takeaways

- Hydrogen has been vital in industry for over a century but faces challenges in production and transportation.

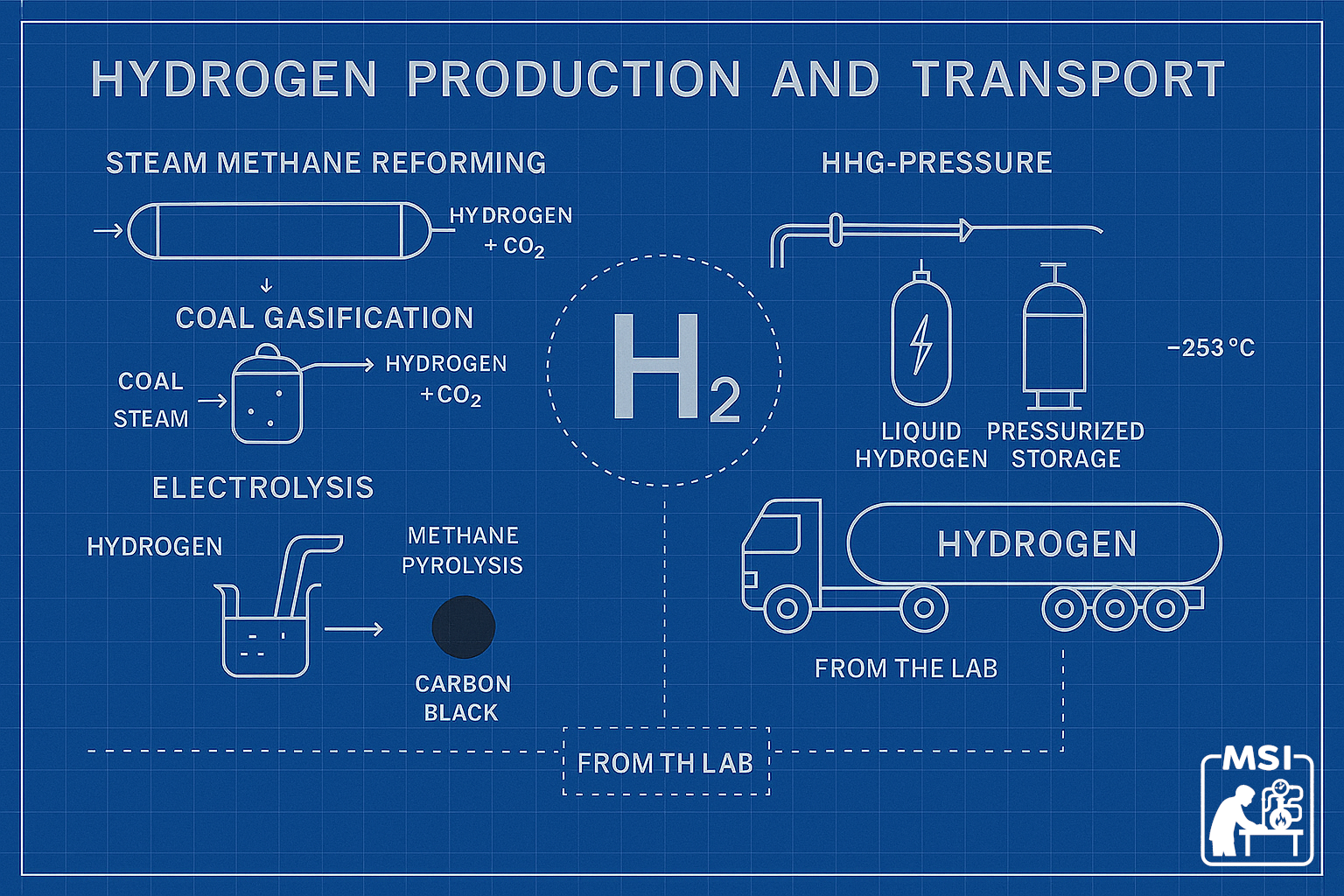

- Traditional methods like Steam Methane Reforming and coal gasification are carbon-intensive, while electrolysis can also be costly unless powered by renewables.

- Emerging methods such as methane pyrolysis and biomass gasification show promise for cleaner hydrogen, but they still require development.

- Transporting hydrogen proves difficult due to its small size and low volumetric energy density, necessitating specialized storage and transport solutions.

- Countries are racing to lead in hydrogen, with goals to build infrastructure and innovate technologies for efficient hydrogen production and transportation.

Hydrogen has been part of the industrial landscape for more than a century, quietly powering refineries, chemical plants, and fertilizer production and has only recently become a headline topic. It seems the world now is just beginning to treat hydrogen as an important source of energy—one that could reshape many industries. However, there are challenges with hydrogen production and transportation. Let’s review!

Traditional Hydrogen Production: How We Got Here

For most of its history, hydrogen has been produced through a handful of well‑established industrial processes. These methods were designed for cost efficiency, not environmental performance, because hydrogen was primarily used as a feedstock—not a fuel. The three dominant production pathways have been:

1. Steam Methane Reforming (SMR)

SMR is the workhorse of global hydrogen production, responsible for the majority of supply. In this process, natural gas (mostly methane) reacts with high‑temperature steam to produce hydrogen and carbon monoxide. A secondary reaction converts the carbon monoxide into carbon dioxide and additional hydrogen.

SMR is a reliable, mature, and relatively inexpensive process. But it comes with a major drawback: for every kilogram of hydrogen produced, roughly 9–12 kilograms of CO₂ are emitted. This “gray hydrogen” has been acceptable for industrial applications, but it is incompatible with the climate goals that are the basis for current interest in H2 as a fuel.

2. Coal Gasification

In regions with abundant coal—China, India, parts of Eastern Europe—coal gasification has historically been a major source of hydrogen. In this process, coal is heated with oxygen and steam under pressure, producing a mix of gasses that can be further separated into hydrogen and CO₂.

Hydrogen from coal is even more carbon‑intensive than SMR, making it the least environmentally favorable pathway. Still, it remains entrenched in certain industrial sectors because of existing infrastructure and low input costs.

3. Electrolysis (Traditional, Not Renewable‑Powered)

Electrolysis splits water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. You may have played with this in a distant science class! While the process itself produces no emissions, the electricity source historically came from the power grid, produced using fossil fuels. As a result, traditional electrolysis was often more carbon‑intensive than SMR unless powered by nuclear or hydroelectric plants.

In recent years, the grid-supplied power has been replaced by wind and solar sources to create “Green Hydrogen” making the process (supposedly) cleaner.

Regardless of the electrical source, electrolysis is expensive—far more costly than SMR—so it has been used only in niche applications where ultra‑pure hydrogen was required.

Emerging Hydrogen Production Methods

There are several new methods of Hydrogen being pursued. These all show promise but are very early in development. And, of course, there are always other ideas being pursued behind closed doors. The methods we know about are:

1. Methane Pyrolysis: Solid Carbon, No CO₂

Methane pyrolysis splits natural gas into hydrogen and solid carbon without emitting carbon dioxide. Unlike SMR, it avoids the need for carbon capture and produces a marketable byproduct—solid carbon for use in tires, batteries, and construction materials.

Pros: Lower emissions, valuable carbon byproduct

Cons: Still early-stage, requires high temperatures and reactor development

2. Biomass Gasification: Waste to Hydrogen

Biomass gasification converts agricultural or forestry waste into hydrogen-rich syngas. When paired with carbon capture, it can be carbon-negative.

Pros: Utilizes waste, rural deployment potential

Cons: Feedstock variability, complex gas cleanup

3. Plasma Reforming and Microwave Catalysis

These experimental methods use plasma arcs or microwave fields to drive hydrogen production from methane or water.

Pros: Potential for high efficiency and modular systems

Cons: Not yet commercial, limited scale testing

4. Photocatalytic and Thermochemical Water Splitting

These methods use sunlight or heat directly to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

Pros: No electricity required, ideal for remote or off-grid use

Cons: Low conversion efficiency, still in lab-scale development

5. Enzymatic and Biological Pathways

Some research explores microbial or enzymatic systems that produce hydrogen from organic matter.

Pros: Low temperature, potentially low cost

Cons: Very slow reaction rates, not scalable yet

Why Transporting Hydrogen Is So Difficult

Producing hydrogen is only half the challenge. Moving it safely and economically is the other half—and this is where hydrogen’s unique properties create issues!

Hydrogen Is the Smallest Molecule in the Universe

Its tiny size allows it to leak through all of the typical components of a tank: Seals, valves, and micro‑fractures that would easily contain other gases leak hydrogen. This means:

- Pipelines require specialized materials or retrofits

- Storage tanks must be engineered for extremely low permeability

- Compression systems must be designed to handle high leak‑risk environments

Hydrogen leakage is not just a safety issue—constantly losing product means the value of the “full” tank is also being lost.

Low Volumetric Energy Density

Hydrogen has exceptional gravimetric energy density—energy per unit of mass— It’s weight! This is why H2 is attractive for aviation, drones, and heavy trucks. However, its volumetric energy density—energy per unit of volume—is extremely low. It takes up a lot of space!

To store or transport meaningful quantities, hydrogen must be:

- Compressed to 350–700 bar.

- Liquefied at –253°C.

- Converted into ammonia or methanol.

- Absorbed into metal hydrides or liquid carriers

Each method adds cost, complexity, and energy loss.

Liquefaction Is Energy‑Intensive

Cooling hydrogen to very low (cryogenic) temperatures consumes 25–35% of the energy contained in the hydrogen itself! This is why liquid hydrogen is used mostly in specialized industrial applications, like aerospace.

Pipeline Compatibility Issues

Hydrogen can cause embrittlement in certain metals, weakening pipelines over time. While some natural‑gas pipelines can be repurposed, many will require reinforcement or replacement.

Transporting Hydrogen by Truck Is Expensive

Transporting hydrogen is a real challenge, caused by it’s physical characteristics: We need to compress it or cool it to create enough density to make transporting it long distances economical. The major setbacks are:

1. Compression Costs

Compressing hydrogen to 700 bar consumes 10–15% of its energy content. Specialized compressors and leak-proof systems add capital and maintenance costs.

2. Liquefaction Losses

Liquefying hydrogen at –253°C consumes 25–35% of its energy. Cryogenic systems are expensive and energy-intensive, making liquid hydrogen viable only for aerospace or high-value applications.

3. Trucking Inefficiency

A diesel tanker delivers 10–15× more usable energy than a hydrogen tube trailer at 250 bar. Even at 700 bar, hydrogen’s low volumetric energy density makes long-haul trucking uneconomical.

4. Pipeline Challenges

Hydrogen embrittles steel, requiring special alloys or composite materials. New hydrogen pipelines can cost $1–1.5 million per kilometer, several times more than natural gas lines.

5. Conversion Tradeoffs

Turning hydrogen into ammonia or methanol improves transport economics but adds conversion losses and reconversion costs. These carriers are useful for export but not ideal for local use.

The appropriate response to these challenges with hydrogen production and transportation is to deploy many on-demand manufacturers near the end-users, to avoid long-term storage, and to compress hydrogen for short-haul delivery. Still, hydrogen will require the design of new transportation tanks.

Hydrogen and the New “Space Race”

Hydrogen has always been the fuel of the space age. Liquid hydrogen powered the Saturn V rockets that carried astronauts to the moon. It remains the propellant of choice for many modern launch systems because of its unmatched specific impulse.

But today’s “space race” is not just about rockets—it’s about energy leadership.

Countries are competing to:

- Build national hydrogen hubs

- Secure supply chains for hydrogen production

- Develop next‑generation hydrogen engines

- Deploy hydrogen fueling corridors

- Dominate global hydrogen exports

Just as the original space race accelerated innovation in materials science, computing, and aerospace engineering, the hydrogen race is accelerating breakthroughs in:

- Catalysts

- Storage materials

- High‑pressure systems

- Cryogenic handling

- Fuel‑cell durability

- Hydrogen‑ICE optimization

- Distributed production technologies

The nations and companies that master hydrogen will shape the next century of transportation, logistics, and energy security.

An Improved Tomorrow

Hydrogen is not a silver bullet, but it could be a powerful tool—one that complements batteries, renewable energy, and advanced combustion technologies. And reduces climate change. As the world pushes toward cleaner energy systems, hydrogen stands out as a versatile, scalable, and future‑proof solution.

The next decade may determine who leads us all into the hydrogen era. Like the space race before it, solving the challenges of hydrogen production and transportation will require deep innovation. The winners will be those who innovate boldly, move quickly, and build the systems that turns possibility into reality.

Further Reading

Brown, A. (2025). Cummins‑Navistar Class 8 fuel cell truck pilot (news coverage). Hydrogen Fuel News. https://www.hydrogenfuelnews.com/cummins-navistar-class-8-pilot

Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. (2025). Methane pyrolysis for hydrogen production. https://www.c2es.org/document/methane-pyrolysis-for-hydrogen-production/

Clean Energy Group. (2025). The drawbacks of liquid hydrogen. Clean Energy Group. https://www.cleanegroup.org/wp-content/uploads/Hydrogen-Liquefaction-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Hydrogen Council & McKinsey & Company. (2021). Hydrogen Insights 2021: A perspective on hydrogen investment, deployment and cost competitiveness. Hydrogen Council. https://hydrogencouncil.com/en/hydrogen-insights-2021/

Hydrogen Generation Technology in 2025: Latest Production Methods and Breakthroughs. (2025). https://kpgroup.co/blog/hydrogen-generation-technology/

International Energy Agency. (2021). Global Hydrogen Review 2021. International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2021

Lotfollahzade Moghaddam, A., Hejazi, S., Fattahi, M., Kibria, M. G., Thomson, M. J., AlEisa, R., & Khan, M. A. (2025). Methane pyrolysis for hydrogen production: Navigating the path to a net‑zero future. Energy & Environmental Science, 18, 2747–2790.

https://doi.org/10.1039/D4EE06191H

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). (n.d.). Renewable electrolysis. NREL / Hydrogen and Fuel Cells. https://www.nrel.gov/hydrogen/renewable-electrolysis.html

Rocketdyne / Historical sources. (n.d.). J‑2 engine and LH2 use on Saturn V. Wikipedia / Rocketry archives. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocketdyne_J-2

Scania. (2025). Scania reveals its first hydrogen trucks in Swiss pilot launch (news coverage). Driving Hydrogen. https://www.hydrogenfuelnews.com/hydrogen-boosted-by-cummins-navistar-class-8-fuel-cell-truck-pilot/8572749/

Sofronis, P., Robertson, I. M., & Johnson, D. D. (2010). Hydrogen embrittlement of pipeline steels: Fundamentals, experiments, modeling (DOE Hydrogen Program Annual Progress Report). U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/docs/hydrogenprogramlibraries/pdfs/progress10/iii_10_sofronis.pdf

Swanger, A. M. (n.d.). NASA‑KSC & liquid hydrogen: Past, present & future. NASA Kennedy Space Center. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20210016332/downloads/London%20SPE%20Review_NASA-LH2_ASwanger.pdf

U.S. Department of Energy, Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office. (n.d.). Hydrogen production: Electrolysis. U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-production-electrolysis

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy. (2020). Hydrogen strategy: Enabling a low‑carbon economy. U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/07/f76/USDOE_FE_Hydrogen_Strategy_July2020.pdf

Volvo Group. (2026). Volvo Group deploys hydrogen trucks across Europe (project announcement / press release). https://fuelcellsworks.com/2026/01/28/fuel-cells/three-new-partners-join-forces-with-volvo-group-to-deploy-hydrogen-trucks-across-europe

Xue, J., & Boukadi, F. (2025). Factors affecting energy consumption in hydrogen liquefaction plants. Processes, 13(8), Article 2611. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13082611.

Yang, M., Hunger, R., Berrettoni, S., Sprecher, B., & Wang, B. (2023). A review of hydrogen storage and transport technologies. Clean Energy, 7(1), 190–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/ce/zkad021

Younus, H. A., Al Hajri, R., Ahmad, N., Al‑Jammal, N., Verpoort, F., & Al Abri, M. (2025).

Green hydrogen production and deployment: Opportunities and challenges. Discover Electrochemistry, 2, Article 32. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s44373-025-00043-9

Yu, L., Feng, H., Li, S., Guo, Z., & Chi, Q. (2025). Study on hydrogen embrittlement behavior of X65 pipeline steel in gaseous hydrogen environment. Metals, 15(6), 596. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0010938X2600034X

Leave a Reply